The United States of America’s Consideration of Ethics and Justice Issues in Formulating Climate Change Policies

Revised December 22, 2014

Donald A. Brown

Scholar In Residence On Sustainability

Ethics and Law and Professor

Widener University School of Law

Dabrown57@gmail.com

This is a revision to the US paper peviously posted on this site which responds to the research questions of the Project On Deepening National Responses to Climate Change On The Basis of Ethics and Justice, a joint project of the University of Auckland, School of Architecture and Planning and Widener University, School of Law, Environmental Law Center.

This revision to the US paper was needed because on November 11, 2014, the United States increased its international commitments on climate change as explained below.

The research questions and responses are as follows:

1. To what extent has the national debate about how the nation should respond to climate change by setting a ghg emissions reduction target expressly considered that the nation not only has economic interests in setting the target but also ethical obligations to those who are most vulnerable to climate change and that any national ghg emissions reduction target must represent the nation’s fair share of safe global emissions? In answering this question, identify the national ghg emissions reduction target, if any, that the nation has made under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

On November 11, 2014 the Obama Administration announced a new US commitment on reducing its ghg emissions in a deal with China. (US White House, 2014) The United States has pledged to cut its emissions to 26-28% below 2005 levels by 2025 while retaining a prior pledge to reduce US ghg emissions by 80 % below 2005 by 2050.

At the same time, President Xi Jinping of China announced targets to peak CO2 emissions around 2030, with the intention to try to peak early, and to increase the non-fossil fuel share of all energy to around 20 percent by 2030.

The US announcement was met with mostly, but not uniformly. positive responses from most nations because the new commitment was a significant increase over the US commitment made in 2009 to reduce US ghg emissions17% reduction commitment below 2005 by 2020. However, as explained below, the United State justification acknowledges the commitment is based upon what is achievable under existing law rather than what may be required of the United States by ethics and justice.

The US justification for its new 2025 commitment is as follows:

The target is grounded in intensive analysis of cost-effective carbon pollution reductions achievable under existing law and will keep the United States on the right trajectory to achieve deep economy-wide reductions on the order of 80 % by 2050. (US White House, 2014)

According the US White House, the 80% reduction commitment by 2050 is based upon a commitment made by the United States to the G8. (Light, 2014)

The US has not asserted that the 26 to 28 % reductions below 2005 emissions reduction commitment by 2025 or 80% reduction below 2005 emissions by 2050 aspiration represents the US fair share of safe global emissions. In regard to the 80% reduction commitment, the United States has asserted that:

The 80% figure was taken from the 2009 G8 Declaration on climate change, especially paragraph 65:

65. [. . .] We recognize the broad scientific view that the increase in global average temperature above pre-industrial levels ought not to exceed 2°C. Because this global challenge can only be met by a global response, we reiterate our willingness to share with all countries the goal of achieving at least a 50% reduction of global emissions by 2050, recognizing that this implies that global emissions need to peak as soon as possible and decline thereafter. As part of this, we also support a goal of developed countries reducing emissions of greenhouse gases in aggregate by 80% or more by 2050 compared to 1990 or more recent years. . .

The Obama administration has thus implicilty acknowledged that the current 2025 commitment is based upon what is currently achievable under existing law rather than on what ethics and justice would require of the United States while the commitment to reduce by 80% by 2050 is based on a promise made to the G8.

Although it is speculation, it would appear that the reference by the United States to a 80% reduction commitment by 2050 originally made to the G8 was influenced by a 2007 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2007, p776) which concluded that developed nations needed to reduce ghg emissions by 25% to 40% below 1990 emissions levels by 2020 and 80% to 95% by 2050 for the world to have any reasonable chance of limiting warming to 2°C. If this is the case, the US government has not explained why the US believes it need only achieve the lower end of the 80% to 95% reduction range goal for 2050 emissions for developed nations identified by the IPCC in 2007 nor why the current commitment of 26% to 28% below 2005 emissions by 2025 is justified given the much higher 25% to 40% reduction targets by 2020 recommended by the IPCC in 2007 for developed nations.

It would also appear when determining any of its ghg commitments that the United States has not considered the most recent carbon budget identified by the IPCC’s 5th Assessment Report (IPCC, 2013, p27). A carbon budget is a limit of total ghg emissions for the entire world that must constrain global emissions to have any reasonable hope of limiting warming to 2°C or any other temperature limit. The IPCC budget is understood to define a limit of future carbon emissions of approximately 270 gigatonnes carbon (GtC) to have a 66% chance of limiting the warming to 2°C (Pidcock, 2013). The 2°C warming limit has been agreed to by the international community including the United States as necessary to prevent potentially catastrophic climate change. The US has agreed several times including in the G8 agreement above on the need for it to adopt policies that will working with others prevent warming from exceeding the 2°C warming limit.

Because any US ghg target is implicitly a position on the US fair share of safe global emissions, any US emissions reduction target may only be justified as a matter of ethics and justice by explaining why the US commitment is a fair share of an acceptable global carbon emissions budget. Yet, the Obama administration has made no attempt to explain or justify other than in very general terms its commitment target in reference to a global carbon budget or a warming limit.

Recently, President Obama also announced a proposed new regulation that would limit emissions from the electricity generation sector by 30% by 2030 (Davenport, 2014). Yet this announcement was made without any explanation of how this reduction amount was linked to the US fair share of safe global emissions. In fact, President Obama justified the new regulation on the basis of how it would protect the health of US citizens. (McCarthy, 2014). In justifying this new regulation on the health of Americans, rather than on reduced potential harms caused by US emissions to hundreds of millions of some of the world’s poorest people who are most vulnerable to climate change, President Obama failed to acknowledge US ethical responsibilities to reduce the threat of climate change to the rest of the world including future generations.

During a speech at Georgetown University in June 2013, President Obama did acknowledge in very general terms that the United States has responsibility for climate change when he said:

[A]s the world’s largest economy and second-largest carbon emitter, as a country with unsurpassed ability to drive innovation and scientific breakthroughs, as the country that people around the world continue to look to in times of crisis, we’ve got a vital role to play. We can’t stand on the sidelines. We’ve got a unique responsibility. (Obama, 2014)

Although President Obama thus acknowledged US responsibility to the world to take effective action on climate change, the US has not explained how this responsibility is linked quantitatively to any ghg mitigation commitments.

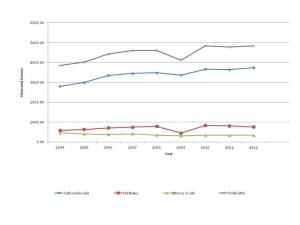

In fact a strong case can be made that the US emissions reduction commitment for 2025 of 26% to 28% clearly fails to pass minimum ethical scrutiny when one considers the implications of the fact that in the US-China agreement announced in November both countries agreed to “equalize” their per capita emissions by 2030. (Narain, 2014) As one observer noted about the fairness of this agreement.

“ [U]nder such an agreement the United States would come down “marginally’ from its current 18 tonnes per capita and China would increase from its current seven-eight tonnes. Both the polluters would converge at 12-14 tonnes a person a year. This is when the planet can effectively absorb and naturally cleanse emissions not more than two tonnes a person a year.”

Because the US commitment on its 2025 emissions reductions of 26% to 28% is simply based on what is achievable under existing law and there is no current willingness of the US Congress to pass laws that would provide for greater ghg emissions reductions, assessing the Congressional debate in the United States reveals current US Congressional unwillingness to upgrade US climate change law has been based on two objections. The debate about climate change in the United States has for over 35 years focused almost exclusively on two kinds of issues. These issues have been framed by opponents of proposed US climate change policies. For the most part the US government and NGOs have responded to these issues while ignoring ethical obligations for US climate change policy.

The first issue has been whether there has been sufficient scientific certainty about human causation of harmful climate change to warrant climate policies given the likely costs of climate change policies to certain sectors of the US economy.

The second issue which has dominated US climate policy debates for the last few decades is based on claims that proposed climate law and policies would impose unacceptable costs on the US economy. The cost arguments have taken several forms. (Brown, 2012b p57)

These arguments have included that proposed climate legislation and policies would destroy jobs, reduce US GDP, damage specific industries such as the coal and petroleum industries, increase the cost of fuel, or simply that proposed climate policies and legislation are unaffordable (Brown, 2012b, p57).

It is clear that the actual justifications for current US positions on climate change are not the reasons given by the Obama administration, which may be doing as much as it can under existing law, but the arguments that have been successfully made to prevent more ambitious US climate change policies by opponents of stronger US climate change policies. We thus conclude that in the US, at least, to determine the justifications for domestic action on climate change it is not sufficient to examine the claims of the government, one must examine the arguments made by opponents of climate change that have successfully blocked stronger action by the government on climate change.

Although both the scientific uncertainty and cost arguments made in opposition to US climate law and policies can be shown to be ethically problematic because they ignore US ethical obligations to others (see Brown, 2012b, pp57–137), these arguments have failed to be examined in the US press or responded to by the US government through an ethical lens. (Brown, 2009; Brown, 2012b). In response to arguments made by opponents to stronger climate change policies that the United States should not reduce its emissions until China does so, for instance, the US government and US NGOs have usually said such things as the world needs US leadership rather than acknowledging that the US has ethical and legal obligations to people and nations who are vulnerable to climate change and that current US emissions are causing and will continue to cause harm unless greatly reduced from current levels.

With very few exceptions, the US press has utterly failed to cover climate change as an ethical and moral issue while focusing on the scientific and economic arguments against taking action that have been framed by opponents of US climate change policies.

By focusing on the cost issues to the US economy, the US press has reinforced the ethically problematic notion that cost to the US economy alone is an acceptable justification for inaction on climate change.

The US debate on climate change has ignored the fact that when the United States ratified the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1992 it agreed that nations:

[H}ave, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations and the principles of international law….. the responsibility to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction or control do not cause damage to the environment of other States or of areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction’ (UNFCCC, 1992, Preamble)

and that nations must:

Protect the climate system for the benefit of present and future generations of humankind, on the basis of equity and in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities. Accordingly, the developed country Parties should take the lead in combating climate change and the adverse effects thereof. (UNFCCC, 1992, Art. 3)

And so the climate debate covered in the US media has consistently largely ignored the fact that US policies should be based upon ‘equity’ and ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ rather than on national economic interest and that the United States has a duty to prevent harm to others. In fact, there has been very little coverage in the US mainstream media of the policy implication of the US promise to reduce its ghg emissions to levels to prevent dangerous anthropogenic climate change based upon ‘equity’ and ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’.

The following issues are almost completely missing from the debate on US climate change policies that has appeared in the US mainstream media:2

** Whether the US has a responsibility to the rest of the world for climate change given:

* US historical emissions;

* US per capita emissions;

* It is the poorest people around the world who are most harmed by climate change.

** What is the US fair share of safe global emissions?

** What is the US responsibility for adaptation costs and compensation for losses and damages in poor nations which have done little to cause climate change?

** Whether the US has responsibility for climate refugees?

** What does ‘equity’ mean under the UNFCCC?

** What ghg atmospheric concentration should any US climate change commitment be designed to achieve?

2. In making a national commitment to reduce ghg emissions under the UNFCCC, to what extent, if at all, has the nation explained how it took equity and justice into consideration in setting its ghg emissions reduction target?

As explained above, the United States government has acknowledged that its most recent commitment is based upon what is currently achievable under US law not on what equity and justice would require of it. There has been no attempt to explain why the US commitment of reducing its emissions by 26% to 28 % by 2025 below 2020 represents the US fair share of safe global emissions.

3. Given that any national ghg emissions target is implicitly a position on achieving an atmospheric ghg concentration that will avoid dangerous climate change, to what extent has the nation identified the ghg atmospheric concentration stabilization level that the national emissions reduction target seeks to achieve in cooperation with other nations?

As explained above, the United States has acknowledged that there is a need to limit warming to 2 0 C but has not explained how its short-term 2025 commitment relates to the carbon budget that will keep the world from exceeding this limit. Its most recent announcement implies that a US reduction of 80% by 2050 would represent the US fair share of safe global emissions but has not explained what equity framework it is relying on to support this conclusion nor why 80% reduction represents the US fair share of a carbon budget. Moreover, there is some scientific evidence that the global warming limit should be lower than 2°C to prevent dangerous climate change.3

4. Given that any national ghg emissions target is implicitly a position on the nation’s fair share of safe global emissions, to what extent has the nation identified the ethical and justice considerations that it took into account in allocating a percentage of global ghg emissions to the nation through the identification of a ghg emissions reduction commitment?

As explained above, the United States government has not explained how the US ghg emissions reduction commitments took into consideration ethics and justice issues in establishing US emissions reduction targets.

Also as noted above, the United States has failed to explain why the United States ghg emissions reductions are consistent with what ‘equity’ or ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ require of it under the UNFCCC.

5. To what extent, if at all, has the nation acknowledged that nations emitting ghg above their fair share of safe global emissions have a responsibility to fund reasonable adaptation measures or unavoidable losses and damages in poor developing countries?

The United States has not acknowledged that a nation emitting above its fair share of safe global emissions has a duty to fund reasonable adaptation measures or losses and damages in developing nations. In fact, US Special Envoy on Climate Change Todd Stern said in 2009:

I actually completely reject the notion of a debt or reparations or anything of the like. For most of the 200 years since the Industrial Revolution, people were blissfully ignorant of the fact that emissions caused a greenhouse effect. It’s a relatively recent phenomenon. (Revkin and Zeller, 2009)

The United States, along with several other developed nations, has strongly opposed the creation of a ‘losses and damages’ mechanism under the UNFCCC, which has recently been strongly advocated for by vulnerable developing nations, if the funding for such a mechanism is derived on the basis of compensation obligations of high-emitting nations (Lefton and Taraska, 2013)

On November 11, 2014, President Obama announced that the United States will contribute $3 billion to a new international fund, the Green Climate Fund, intended to help the world’s poorest countries address the effects of climate change. (Davenport and Landler, 2014) Since 2010, the Obama administration has spent about $2.5 billion to help poor countries adapt to climate change and develop clean sources of energy, (Davenport and Landler, 2014) The US explanation for its most recent contribution to the Green Climate Fund was that it “is in our national interest to build resilience in developing countries to climate change.’ (Davenport and Landler, 2014) And so the US justification for funding adaptation in developing nations is national interest rather than global responsibility. Given the enormous costs of adaptation and losses from climate change induced storms, one storm Hurricane Sandy for instance has cost at least $ 5 billion alone to the US (Porter, 2013), a strong case that current US commitments for costs of mitigation, adaptation, losses, and damages in developing countries is far short of the US legal and ethical obligations to fund these needs in developing countries.

6. What formal mechanisms are available in the nation for citizens, NGOs and other interested organizations to question/contest the nation’s ethical position on climate change?

The United States regularly meets with interested NGOs before and during climate negotiations under the UNFCCC although comments in such meetings are informal. When the United States government develops domestic regulations under US law, citizens have a right to comment and the US government must respond to comments on the proposed regulations. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently announced procedures for citizens to submit formal comments and testify on proposed climate change regulations for power plants (US EPA, 2014).

7. How is the concept of climate justice understood by the current government? Have they articulated any position on climate justice issues that arise in setting ghg emissions policy or in regard to the adaptation needs of vulnerable nations or people?

As explained in previous answers, the United States has not explained its position on climate justice issues except to deny responsibility for losses and damages as noted in answer to question 5. The US government has supported raising money for the adaptation needs of developing countries but not as a matter of any US compensation obligations.

8. Are you aware of any regional, state, provincial, or local governments in your country that have acknowledged some ethical responsibility for climate change? If so, what have they said?

Many US cities and at least 30 US states have adopted climate change action plans (C2ES, 2011), and 22 US states have established ghg emissions reductions targets (C2ES, 2011). US states’ emissions reduction targets vary widely from state to state. Some states have only short-term ghg reduction targets, while some states have short-and long-term targets although some states with long-term targets have no long-term target date (C2ES, 2014). However, California, Connecticut, Colorado, Florida, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey and New York have committed to reducing ghg emissions by 80% by 2050 although they use different baseline years in achieving this goal (C2ES, 2014). Those states which have committed to the 80% reduction levels have not explained in the publicly available documents how they have taken into account ethics and justice issues in determining their target.

Two states, New York and California, however, have somewhat acknowledged the need to consider ethics and justice in formulating climate change policy. For instance, during the formulation of climate policy, New York acknowledged the need to consider equity when it said:

Determining how much individual states or nations should reduce emissions through mid-century requires consideration of allocation equity and reduction effectiveness. The UNFCCC approach to apportioning GHG emission reduction requirements between developed and developing nations considers a broad spectrum of parameters, including population, gross domestic product (GDP), GDP growth, and global emission pathways that lead to climate stabilization. Applying these parameters, the UNFCCC concludes that, to reach the 450ppm CO2e stabilization target, developed countries need to reduce GHG emissions by 80 to 95 percent from 1990 levels by 2050. (New York State, 2009)

Yet when New York set a ghg target in 2009, it set a target of 80% below 1990 levels by 2050 without explaining how it took ethics and justice into account despite its recognition that ethical and justice considerations might require up to a 95% reduction by 2050 (C2ES, 2014).

Although a California statute expressly requires California to consider environmental justice issues in setting climate change policies, this law is focused on justice issues that affect the United States and its domestic population rather than global environmental justice.4

The US EPA has developed an outreach programme for US state and local governments which includes guidance on how to develop ghg inventories and action plans, but none of this guidance identifies the need to consider equity, justice, or ethics in setting ghg policies (USEPA, 2014b).

One thousand and sixty US cities have agreed to develop climate action plans and set emissions reduction targets that support the US achieving its national target of reducing emissions by 17% below 2005 by 2020 (U.S. Conf, 2014). According to the International Council of Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI), an organization which supports climate change planning by local governments, 204 US local governments also set additional specific ghg reduction targets (ICLEI, 2010, pp40–42). These targets vary greatly in their ambition, with some being quite modest, although 34 US local governments have set long-term targets of at least 80% reductions by 2050, and Annapolis, Maryland and Northfield, Minnesota have promised to be carbon neutral by 2050 and 2033 respectively (ICLEI, 2010, p41). The publicly available descriptions of these targets do not reveal which of these cities, if any, considered ethics and justice when setting the target.

9. Has your national government taken any position on or otherwise encouraged individuals, businesses, organizations, subnational governments, or other entities that they have some ethical duty to reduce greenhouse gas emissions?

As mentioned in answer to the previous question, the US EPA provides guidance on reducing ghg emissions to subnational entities. This guidance also supports individuals who wish to reduce their ghg emissions by providing an individual ghg calculator and identifying steps that an individual can take to reduce one’s carbon footprint (US EPA, 2014c). Yet this guidance does not include any encouragement to consider ethical and justice issues in setting individual ghg goals.

10. What recommendations would you make to get the nation or civil society to take ethics and justice issues seriously in climate change policy formulation?

The utter failure of the US government and mainstream media to expressly discuss and consider ethics and justice issues when formulating climate change policies can be attributed to the following causes according to Brown (2012b):

**The power of the climate change denial industry and other opponents of climate change policies with economic interests in fossil fuel production or consumption to frame climate change policy issues.

**The dominance of ‘value-neutral’ policy languages, particularly economics, to frame climate change policy issues without critical reflection from the press or US NGOs on the ethically problematic assumptions often hidden in these analyses.

**The failure of higher education in the United States to train environmental professionals to spot ethical issues that arise in environmental policy formation.

**The failure of departments of philosophy and academic environmental ethics institutions to focus on ethics issue spotting in actual policy arguments.

**The failure of civil society, including US NGOs who are proponents of climate change policies, to identify ethical questions about policy matters.

There is little hope that the US government will consider the ethics and justice issues entailed by climate change that are relevant to US climate policy unless more US citizens better understand why climate change raises civilization-challenging ethical issues that have practical significance for policy and call for the United States to acknowledge its ethical and justice responsibilities in determining US climate policy.

Yet to really understand these issues, one must understand that:

**The mainstream scientific community has concluded that to prevent dangerous climate change the world must constrain global ghg emissions by a global carbon budget which will limit warming to acceptable levels.

**The total acceptable emissions entailed by the budget must be allocated among all nations in the world.

**Some nations and people much more than others have been putting poor nations and people at great risk.

**Achieving an adequate global solution to climate change will require high-emitting nations, organizations, subnational governments, organizations, businesses and individuals to reduce their ghg emissions at much greater levels than others.

To generate this wider understanding, the US press must begin to cover the policy implications of the climate change ethics and justice issues. To achieve greater US media coverage of these issues, higher education and US NGOs must put the ethics and justice dimensions of climate change near the top of their agenda and demand that the US government and media acknowledge the ethical and justice dimensions of climate policy issues including but not limited to ethical issues that arise in setting ghg emissions reduction targets and national responsibility for adaptation and for losses and damages in poor, vulnerable countries.

US NGOs must also demand that the US government articulates how any US ghg emissions reduction target seeks to achieve an atmospheric ghg stabilization goal that protects those most vulnerable to climate change and how any percentage reduction in a US ghg reduction target has taken into account issues relevant to a US fair national ghg allocation including national per capita emissions and historical emissions.

Notes

1 See Brown, 2002, pp13–48 for a detailed history of the US climate debate from 1970 through 2001; Brown, 2012b, pp20–53 for a detailed history of the US climate debate from 2002 to 2012.

2 The conclusions in this section are derived from well over 40 articles in Ethics and Climate, a blog on climate change ethics which has followed the US climate debate from January 2007 until the present (Brown, 2007–2014). For instance, under the Start Here and Index Tab of ethicsandclimate.org there are 16 articles on the failure of the US press to identify the ethical and justice dimensions of climate change during this period. Other articles on how the United States government has ignored the ethical and justice dimensions of climate change can be found among the 140 articles on ethicsandclimate.org.

3 See, for example, the statement of Christina Figueres, Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC, that the warming limit should be 1.5°C (Harvey, 2011).

4 For a discussion of the California statutory provision requiring consideration of environmental justice, see Kaswan, 2008.

References:

American Farmland Trust (2014) ‘Myths and facts surrounding climate change legislation’, http://www.farmland.org/documents/climatechangemythandfact-AmericanFarmlandTrust_002.pdf, accessed 22 July 2014

Brown, D. (2002) American Heat: Ethical Problems with the United States’ Response to Global Warming, Roman and Littlefield, Latham, Maryland

Brown, D. (2007–2014) Ethics and Climate blog, http://blogs.law.widener.edu/climate/, accessed 23 July 2014

Brown, D. (2008) ‘Nations must reduce greenhouse gas emissions to their fair share of safe emissions without regard to what other nations do’, http://blogs.law.widener.edu/climate/2008/06/08/nations-must-reduce-greenhouse-gas-emissions-to-their-fair-share-of-safe-global-emissions-without-regard-to-what-other-nations-do/, accessed 25 July 2014

Brown, D. (2009) ‘The most crucial missing element in U.S. media coverage of climate change: The ethical duty to reduce GHG emissions’, ThinkProgress, 14 August 2009, http://thinkprogress.org/climate/2009/08/14/204506/media-climate-ethics-reduce-ghg-emissions/, accessed 22 July 2014

Brown, D. (2012a) ‘The US media’s grave failure to communicate the significance of understanding climate change as a civilization challenging ethical issue’, ethicsandclimate.org, http://blogs.law.widener.edu/climate/2012/10/31/the-us-medias-grave-failure-to-communicate-the-significance-of-understanding-climate-change-as-a-civilization-challenging-ethical-issue/, accessed 22 July 2014

Brown, D. (2012b) Navigating the Perfect Moral Storm: Climate Change Ethics in Light of a Thirty-Five Year Debate, Routledge-Earthscan, New York

Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES) (2011) ‘Local Action’, http://www.c2es.org/docUploads/climate101-local.pdf

Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES) (2014) ‘Greenhouse Gas Emissions Targets’, http://www.c2es.org/us-states-regions/policy-maps/emissions-targets, accessed 22 July 2014

Davenport, C. (2014) ‘Obama to take action to slash coal pollution’, The New York Times, 1 June, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/02/us/politics/epa-to-seek-30-percent-cut-in-carbon-emissions.html?_r=0, accessed 22 July 2014

Davenport, C. & Lander, M. (2014), ‘U.S. to give $3 billion to climate fund to help poor nations, and spur rich ones’, New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/15/us/politics/obama-climate-change-fund-3-billion-announcement.html?_r=0, accessed 24 Dec. 2014

Freedman, A. (2013) ‘IPCC report contains “grave” carbon budget message’, Climate Central, 4 October, http://www.climatecentral.org/news/ipcc-climate-change-report-contains-grave-carbon-budget-message-16569, accessed 22 July 2014

Harvey, F. (2011) ‘UN chief challenges world to agree tougher target for climate change’, The Guardian, 1 June, http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/jun/01/climate-change-target-christiana-figueres, accessed 21 July 2014

Hossol, J. (2007) ‘Presidential Climate Action Project, Questions and Answers, Emissions Reductions Needed to Stabilize Climate’, The White House, http://www.climatecommunication.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/presidentialaction.pdf, accessed 22 July 2014

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2007) 4th Assessment, Working Group III, Chapter 13, p776, http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg3/en/contents.html, accessed 22 July 2014

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2013) Working Group I, The Physical Science Basis, Summary for Policymakers, http://www.climatechange2013.org/images/report/WG1AR5_SPM_FINAL.pdf, accessed 22 July 2014

International Council on Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI) (2010) Empowering Sustainable Communities, http://www.icleiusa.org/about-iclei/annual-reports, accessed 21 July 2009

Kaswan, A. (2008) ‘Environmental Justice and Domestic Climate Policy’, Environmental Law Reporter, 38 ELR, 30287, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1077675, accessed 23 July 2014

Light, A. (2014) Communication with Donald A. Brown in response to question about the justification for US position.

McCarthy, T. (2014) ‘Obama says carbon pollution caps will “protect health of vulnerable”’, The Guardian, 2 June 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/jun/02/obama-climate-change-carbon-emissions-live, accessed 22 July 2014

Narain, S.. (2014) The bad China-US climate deal, Business Standard, http://www.business-standard.com/article/opinion/sunita-narain-the-bad-china-us-climate-deal-11411230

Netherlands Environmental Agency (NEA) (2012) ‘Trends in global CO2 emissions; 2012 report’, http://www.pbl.nl/en/publications/2012/trends-in-global-co2-emissions-2012-report, accessed 22 July 2014

New York State (2009) Climate Change Issue Brief, New York Energy Plan 2009, www.nysenergyplan.com/final/Climate_Change_IB.pdf#sthash.eMLWTwTq.dpuf, accessed 11 May 2013

Meyers, S. and Kulish, M. (2013) ‘Growing Clamor About Inequities of Climate Crisis’, The New York Times, 16 November 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/17/world/growing-clamor-about-inequities-of-climate-crisis.html?_r=1&, accessed 22 July 2014

Obama, B. (2014) ‘Remarks by the President on Climate Change’, Georgetown University, White House Press Office, 25 June, http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/06/25/remarks-president-climate-change, accessed 22 July 2014

Porter, D. (2013) ‘Hurricane Sandy was second costliest in US history report show, Huffington Post, Feb.12, 2013, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/02/12/hurricane-sandy-second-costliest_n_2669686.html, accessed 24 December 2013

Revkin, A. and Zeller, T. (2009) ‘U.S. Negotiator Dismisses Reparations for Climate’, The New York Times, 9 December 2009, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/10/science/earth/10climate.html#sthash.nUpS8vGX.dpuf.dpuf, accessed 22 July 2014

Romm, J. (2009) ‘The United States Needs a Tougher Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction Target for 2020’, Center for American Progress, 13 January, http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/green/report/2009/01/13/5472/the-united-states-needs-a-tougher-greenhouse-gas-emissions-reduction-target-for-2020/, accessed 22 July 2014

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (1992) 1771 UNTS 107; S. Treaty Doc No. 102-38; U.N. Doc. A/AC.237/18 (Part II)/Add.1; 31 ILM 849

U.S. Conference of Mayors (U.S. Conf) (2014) ‘Cities That Have Signed On’, date undetermined, http://www.usmayors.org/climateprotection/climatechange, accessed 21 July 2014

United States Department of Energy (US DOE) (2009) ‘President Obama Sets a Target for Cutting U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions’, EERE News Archives & Events, 2 December, http://apps1.eere.energy.gov/news/news_detail.cfm/news_id=15650, accessed 17 July 2014

United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) (2014a) ‘How to Comment on the Clean Power Plan Proposed Rule’, date undetermined, http://www2.epa.gov/carbon-pollution-standards/how-comment-clean-power-plan-proposed-rule, accessed 22 July 2014

United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) (2014b) ‘Local Climate and Energy Program’, date undetermined, http://www.epa.gov/statelocalclimate/local/index.html, accessed 22 July 2014

United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) (2014c) ‘Individual Greenhouse Gas Emissions Calculator’, date undetermined, http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/ghgemissions/individual.html, accessed 22 July 2014

United States Information Agency (US EIA) (2013) International Energy Statistics, ‘Per Capita Carbon Dioxide Emissions from the Consumption of Energy (Metric Tons of Carbon Dioxide per Person)’, http://www.eia.gov/cfapps/ipdbproject/iedindex3.cfm?tid=90&pid=45&aid=8&cid=regions&syid=1980&eyid=2010&unit=MMTCD, accessed 22 July 2012

US White House, (2014), FACT SHEET: U.S.-China Joint Announcement on Climate Change and Clean Energy Cooperation, http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/11/11/fact-sheet-us-china-joint-announcement-climate-change-and-clean-energy-c, accessed 24 Dec 2014

World Resources Institute (WRI) (2014) ‘Cumulative Emissions’, Chapter 6 in Navigating the Numbers: Greenhouse Gas Data and International Climate Policy, date undetermined, http://pdf.wri.org/navigating_numbers_chapter6.pdf, accessed 22 July 2014