Linn Energy, LLC, SEC No-Action Letter (publicly available Aug. 30, 2012),

2012 SEC No-Act. Lexis 428, 2012 WL 3835914

Professor Larry D. Barnett

In Linn, a Delaware limited-liability company (company #1) that had issued NASDAQ-listed securities to raise capital for its business operations[i] created a separate Delaware limited-liability company (company #2) that would also issue NASDAQ-listed securities. Tax-exempt entities, as well as persons located outside the United States, were deterred by U.S. tax law from investing in the securities of company #1 because under U.S. tax law the company was deemed a partnership. The tax disincentive would not exist for these entities/persons if they invested in the securities of company #2, however, because company #2 would be classified as a corporation. Company #2 would sell its securities publicly and use the money received from the sale to acquire newly issued securities of company #1, thereby enlarging the investor base of company #1 and providing company #1 with additional capital. Company #2 would have no long-term assets other than securities issued by company #1, and its short-term assets would be cash or cash-equivalents. The raison d’etre of company #2, therefore, was to provide a conduit for investments in company #1: Through ownership of the securities of company #2, persons disadvantaged by U.S. tax law when they directly owned the securities of company #1 could indirectly own the securities of company #1 and avoid the tax consequences of direct ownership. Because the arrangement had specific features that attempted to equalize the governance and economic positions of investors in the two companies, the position of investors in company #1 and the position of investors in company #2 would differ mainly in terms of U.S. tax law.

An issuer of securities that qualifies as an investment company is required by § 7(a) of the Investment Company Act (“Act”) to register with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Company #2, as an issuer of securities that invested in securities, evidently satisfied § 3(a)(1) of the Act, the section that specifies the activities and assets that define an investment company. The request for a no-action letter submitted to the Commission thus focused on whether company #1 was an investment company under § 3(a)(1) and argued that it was not. However, in responding to the request, the S.E.C. Division of Investment Management exempted not only company #1 but also company #2 from § 7(a).[ii] Regrettably, the Division only provided assurance that it would not recommend enforcement action under the Act. No explanation of pertinent law was explicitly given. Indeed, the Division pointed out that it was not “express[ing] any legal or interpretive conclusion on the issues presented.”

Law-specific reasoning for a resolution of an issue of law under the Investment Company Act is typically absent from no-action letters written by the Division of Investment Management. In this regard, then, Linn is not unusual. However, the reply of the staff is notable for what the Division asserted in a footnote. Specifically, the footnote stated that the position taken by the Division in the instant case applied to, and only to, company #1 and company #2. Warning that “no other entity may rely on this position,” the Division observed that the two companies and their proposed arrangement were involved in a situation that had a “very fact-specific nature.” In the view of the Division, its decision dealt with a situation that had unique attributes and hence could not — and should not — be generalized to other settings.

The warning given by the Division should be considered in conjunction with the omission by the Division of its reasoning on whether § 3(a)(1) applied to company #1. The request for a no-action letter had presented a detailed analysis in support of the contention that company #1 was not an investment company. According to the request, company #1 did not meet the criteria established either by § 3(a)(1)(A) or by § 3(a)(1)(C). When it exempted company #1 from § 7(a), did the Division believe that company #1 failed to satisfy one or more of the criteria in each of these sections and hence was not an investment company? Or did the Division think that company #1 qualified as, or might qualify as, an investment company under § 3(a)(1)(A) or § 3(a)(1)(C) but conclude that the proposed arrangement did not undermine the purposes of the Act? One of two routes could thus have been taken in reaching the conclusion that enforcement action was unnecessary under § 7(a) with respect to company #1. Although the route that the Division actually followed is unknown, the warning given by the Division in its reply may be evidence that the second route was chosen, i.e., that the staff thought that company #1 was or might be an investment company, but on policy grounds ruled that the two companies were entitled to an exemption from § 7(a). Such a warning has traditionally been uncommon in no-action letters,[iii] and its inclusion in the instant letter is plausibly an indicator that the staff anticipated that the purposes of the Act would be subverted if the position it took could be widely followed by investment companies.

If the above reasoning is correct, what might explain the concern of the staff? In granting the request of the two companies, the Division exempted from registration not just company #1, but also company #2. Company #2, however, seems to have been an investment company. Therefore, company #2, like company #1, was able to avoid the obligations that the Act imposes on a registered investment company, and company #1 was not subject even to the restrictions that the Act places on an affiliate of a registered investment company.

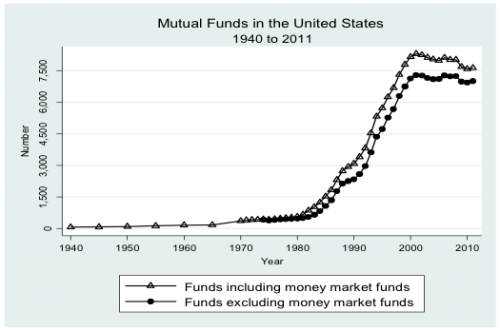

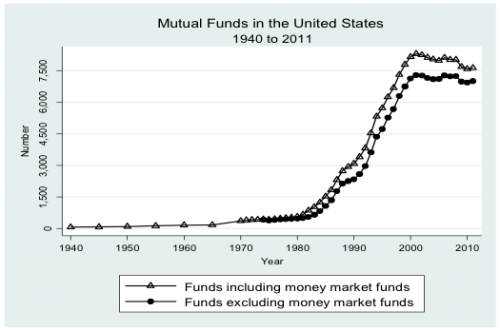

Vehicles for collective investments in securities became much more numerous in the United States during the past three decades, as seen in the graph in the Appendix infra,[iv] and they are now of inestimable significance to the U.S. financial system.[v] As a result, the formulation of law on investment companies can have major consequences for the country — consequences that are economic and, at least as importantly, consequences that are social.[vi] Unless exemptions from the registration requirement of the Act are granted sparingly, the goals that Congress established for the Act are unlikely to be achievable. With this in mind, the staff may have placed the warning in the reply because it harbored doubts, or at least was uncertain, about the contention that company #1 was not an investment company.[vii] Company #1, therefore, may have been an investment company, as was company #2. If so, the exemption of both companies from registration as investment companies could have been prompted by a pair of specific considerations that alleviated the concern of the staff — the securities issued by company #1 had already been sold publicly, and company #2 would be an alter ego of company #1.[viii] Assuming that the exemption was based on these considerations, the grounds for the exemption were indeed narrow, and Linn is likely to have helped the Act maintain its social productivity, the main function of law in a democracy.[ix]

APPENDIX

ENDNOTES

[i] Company #1 purchased and developed properties that contained substantial reserves of oil and natural gas. All of its current property holdings were in the United States.

[ii] Even if it was not an investment company, company #1 would have been subject to § 17(d) of the Act and Rule 17d-1(a) under the Act as long as company #2 was an investment company and was required to register. Joint undertakings by a registered investment company and its first- and second-tier affiliates are covered by § 17(d) and Rule 17d-1(a) when the affiliates are principals in the undertakings. Because company #2 was controlled by company #1 and would own more than 5% of the outstanding voting securities of company #1, company #1 would be a first-tier affiliate of an investment company (company #2) pursuant to § 2(a)(3)(B) and § 2(a)(3)(C) of the Act.

[iii] In a search done on September 8, 2012 of the Lexis database of SEC no-action letters, I looked for the warning in letters that were issued under the Investment Company Act from calendar year 2000 onward. The warning was not found before 2007, and of the 70 no-action letters that carried the warning, fully 90% appeared in 2008 and 2009. Before and after 2009, consequently, few no-action letters issued under the Act included the warning.

[iv] The graph is limited to mutual funds, because as measured by assets under management, mutual funds are currently the most important type of U.S. investment company. Infra note v. The graph was prepared from data in Investment Company Institute, 2012 Investment Company Fact Book 134, 138 (52d ed. 2012), www.icifactbook.org (last visited Sept. 9, 2012).

[v] The latest data on the number and net assets of U.S. investment companies are given below by type of investment company. The data in the columns and in the rows of the table are drawn from different points in time, but all of the time points are within the period from December 31, 2011 to July 31, 2012.

| Type of investment company |

Number |

Net assets |

| Mutual funds |

7,637 |

$12.340 trillion

|

| Closed-end funds |

634 |

$ 0.250 trillion |

| Exchange-traded funds |

1,228 |

$ 1.192 trillion |

| Unit investment trusts |

6,022 |

$ 0.060 trillion |

Source: Investment Company Institute, http://www.ici.org/research#statistics and http://www.ici.org/research#fact_books (last visited Sept. 8, 2012).

[vi] Larry D. Barnett, The Place of Law: The Role and Limits of Law in Society 49–63, 121–22 (2011).

[vii] The subsidiaries of company #1 were wholly owned, not majority-owned. See §§ 3(a)(24), 3(a)(43) of the Act (defining “majority-owned subsidiary” and “wholly-owned subsidiary”). The conclusion that company #1 was an investment company could thus have been based on § 3(a)(1)(C) of the Act, which requires inter alia that, to be an investment company, an entity must own, hold, or trade “investment securities.” Under § 3(a)(2) of the Act, “investment securities” include securities issued by wholly owned subsidiaries.

Although an entity that qualifies as an investment company under § 3(a)(1)(C) may have an exemption from the status of investment company through § 3(b) of the Act, neither the incoming letter nor the staff reply mention, let alone discuss, § 3(b).

[viii] Being exchange-listed, the securities issued by company #2, as well as the securities issued by company #1, were by definition available to the public.

[ix] Barnett, supra note vi, at 198–204.